|

|

August 5, 2005

WBZ: 65 Years in Hull, part I

By SCOTT FYBUSH

It's

been almost five years since Tower Site of the Week burst

forth on an unsuspecting world, and in that time we've visited

sites as far afield as Paris, Bonaire, Tijuana and Nome. Yet

somehow, this column has yet to profile a few of the sites nearest

and dearest to your editor's heart. This week, we'll fix at least

one of those glaring omissions.

It's

been almost five years since Tower Site of the Week burst

forth on an unsuspecting world, and in that time we've visited

sites as far afield as Paris, Bonaire, Tijuana and Nome. Yet

somehow, this column has yet to profile a few of the sites nearest

and dearest to your editor's heart. This week, we'll fix at least

one of those glaring omissions.

From 1992 until 1997, your editor worked for WBZ (1030) in Boston, in the process developing a healthy respect for the history and legacy of one of the nation's oldest and most important radio stations. In future installments of this column, we'll spend some time poking around the sprawling studio complex in Boston's Allston neighborhood that's been home to WBZ and its sister stations for well over half a century.

Within the walls of 1170 Soldiers Field Road, though, you'd be hard-pressed to find more than a handful of people who've laid eyes on the transmitter facility that powers WBZ's huge signal. One can make a good case that there's no other major market where a single AM signal is as clearly superior to all others as WBZ's is in Boston, and one good reason why that's so is the remote location of the WBZ transmitter site.

Leave the WBZ studios, even outside of rush hour, and you'll spend the better part of an hour driving through the city of Boston, down the South Shore and then out several miles of local roads before you reach the small town of Hull, Massachusetts, which sits on a skinny peninsula that juts into Massachusetts Bay. On the west shore of that peninsula, you'll find Newport Avenue, and there, in a neighborhood of modest Cape-style homes, facing out over a dozen miles of bay and, far to the west, downtown Boston, you'll find the site that WBZ has called home since 1940.

WBZ was finishing out its second decade on the air by then, and its history had already taken it from its 1921 beginnings at the Westinghouse plant in East Springfield (that facility remained on the air in 1940 under the WBZA calls) to the Hotel Brunswick in Boston (the original holder of the WBZA calls) to a modern 50,000-watt facility in Millis, some 25 miles southwest of Boston. It was with the 1931 move to Millis that WBZ truly became a Boston station, relegating Springfield to satellite-transmitter status.

Millis, however, was far from an ideal transmitter site. While it was chosen, apparently, for its central location in the triangle bounded by Boston, Worcester and Providence, its signal in Boston suffered from the long land path the signal had to traverse. When the Millis site went into service, good engineering practice dictated that high-power transmitters (15,000 watts when Millis signed on in 1931) should be located at long distances from central cities in order to avoid overloading primitive receivers with poor selectivity. The stations that followed those guidelines quickly discovered that many of those sites (WABC and WJZ in central New Jersey, WGN in Elgin, WHAM in Victor, and so on) were simply too far from their desired audiences to be useful.

So it was that a number of those stations moved again within the decade that followed, which explains why a great number of the big clear-channel giants all have transmitter plants that date from around 1940.

In the case of WBZ, there may have been more at stake as well. Westinghouse was a leader in new broadcast technologies in that era, and its interests included not only AM radio but also the emerging FM medium and the use of shortwave radio, which it had pioneered at KDKA in Pittsburgh. The site at Hull, with a broad expanse of marshy land trailing off into the bay, provided plenty of space for the antennas that the shortwave operation needed.

By moving to Hull, with substantially its entire listening audience to the west, WBZ was also able to take advantage of the new science of directional AM antennas. While the station enjoyed the best possible allocations classification (what would soon be known as a "I-A clear channel), allowing it to run 50,000 watts day and night without directionalizing its signal, its engineers realized that a simple cardoid pattern at Hull would reduce the amount of signal wasted over the Atlantic Ocean while increasing its field strength in densely-populated metro Boston. Only a handful of other "optional" directional arrays were ever built: WTAM in Cleveland and KNX in Los Angeles eventually returned to non-directional operation, and today only WWL in New Orleans and WBZ in Boston are directional I-A clears.

(An amusing digression: many decades later, an FCC inspector visited WBZ for a routine inspection. As he would do at any directional AM, the inspector asked to see the list of monitoring points the station used to ensure its array was in compliance. It took some explaining, a WBZ engineer would recount later on, to persuade the inspector that WBZ had no monitoring points, as it had no obligation to protect any station in its nulls and, indeed, no obligation to operate with a DA at all.)

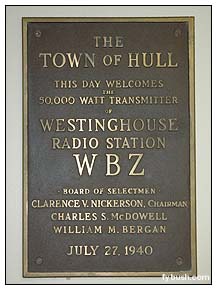

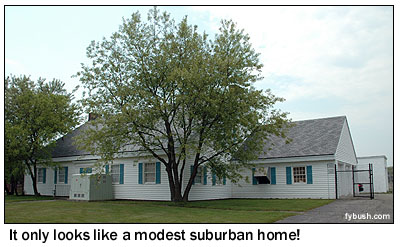

The

facility that Westinghouse dedicated in Hull on July 8, 1940

was intentionally modest in design. In a time when many transmitter

buildings were Art Deco showplaces, the Hull facility was built

to resemble the other Cape Cod-style homes on the residential

street it faces.

The

facility that Westinghouse dedicated in Hull on July 8, 1940

was intentionally modest in design. In a time when many transmitter

buildings were Art Deco showplaces, the Hull facility was built

to resemble the other Cape Cod-style homes on the residential

street it faces.

To the north of the transmitter building, two 500-foot towers were erected, each a half-wave tall on the station's frequency of 990 kHz, and spaced a quarter-wave apart. (The March 1941 shift to 1030 would make the towers, and their spacing, slightly more than half-wave and quarter-wave, respectively.) To the west, a field of telephone poles stretched into the marsh, carrying the antennas for Westinghouse's shortwave operations. (The shortwave station associated with WBZ, first at Springfield and then at Millis, had used the calls W1XK, then WBOS; with the completion of the Hull facility, Westinghouse moved its Pittsburgh shortwave transmitters, then operating as WPIT, to Hull as well. The WPIT calls were retired early in 1941 and the facility was then known solely as WBOS for its remaining years.)

Hull apparently also became the home, for a time, of WBZ's FM operation, which also moved from Millis. The antenna for W67B (46.7 mc) would have most likely been mounted on one of the AM towers; it's hard to imagine that coverage into Boston from such a distance would have been very good, and the FM was quickly relocated to the new TV tower at Soldiers Field Road as that facility was completed in 1948.

After almost twenty years of nonstop motion, WBZ had found a permanent home for its huge AM signal, and a most successful one at that. With nothing but salt water between the bases of its towers and the shoreline of Boston, the Hull site provided - and continues to provide - a booming signal to the city itself. With no nulls to the south and west, unlike Boston's other AM stations, WBZ blanketed the rural areas that would someday become booming suburbs, and which other AMs would struggle to reach successfully. The coastal site gave WBZ a huge reach along the water, pumping a strong daytime signal north into Maine and south into Rhode Island. Its clear channel and tall towers gave WBZ's night skywave signal a spectacular reach, with a particularly strong signal into New York City after dark. Only the outer reaches of Cape Cod, on the back side of WBZ's directional pattern, suffered from a less-than-optimal signal - and in 1940, who knew that would be important?

(One more historical digression: It's not commonly known that the Cape Cod problem was almost solved. As WBZ and other clear channel stations pressed for much higher powers well into the sixties, Westinghouse informed the Congressional subcommittee studying the situation that it would, if granted 750 kW, build a new WBZ transmitter plant in Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, some 50 air miles from downtown Boston. Such construction in an environmentally-sensitive area would be unimaginable today; as it turned out, Congress rejected any increase in power for the clears, making the issue moot.)

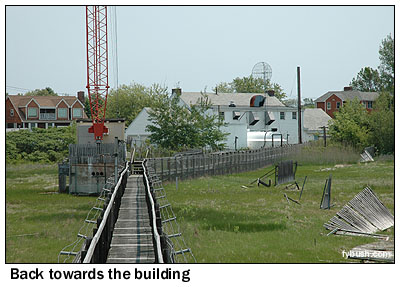

The Hull site was also an excellent one for the WBOS shortwave operation, which targeted its signals to listeners in Europe and South America. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, WBOS and the other commercial shortwave stations around the country were commandeered by the Office of War Information, which took over programming them with what would eventually become the Voice of America. Westinghouse continued to operate the WBOS facility under contract to the government until 1953, when its usefulness came to an end. The transmitters went down the coast to another private shortwave operation, WRUL in Scituate (later WNYW, and now Family Radio's WYFR in Okeechobee, Florida), while the antennas in the swamp were left to rot. As late as 1999, many of the old telephone poles that held WBOS' antennas could still be seen behind the WBZ transmitter building, though most were removed during tower construction that year.

|

|

So with all that history under our belts, let's head out to Hull to see what this venerable site looked like in June, 2005, shall we?

The building itself looks little different now than it would have 65 years ago: from the front, it resembles the other small homes on the street, with the chain-link fence and the big transformer out front some of the only clues that something different is happening inside. The entrance these days is at the back of the building, where it rises to two stories.

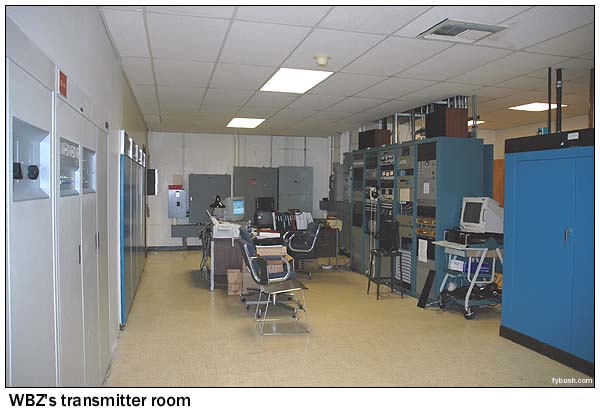

Walk inside, and you're facing right into the main transmitter room:

Not much has changed here in the decade or so since your editor last paid a visit, with the exception of the transmitter at the far left. In 1994, that was one of an identical pair of Harris MW50s, which had in turn replaced the classic Westinghouse 50HG. Today, that MW50's in pieces, soon to be gone, and there's a DX50 in its place to serve as the main transmitter, with the remaining MW50 as backup.

(WBZ is one of the few stations with a completely separate backup transmitter site as well; at the Allston studios, there's a DX10 feeding a folded unipole on the STL tower in the parking lot. That site saw a lot of use during the tower rebuild in Hull in 1999; more on that in a moment.)

|

|

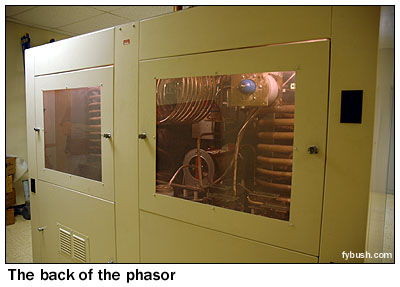

Across from the transmitters sit the big rack of processing and STL gear (the signal now arrives by T1, after many years of struggles with a long and challenging microwave path from Allston that suffered from having downtown Boston in the way, not to mention the propagation issues over all that water), and next to the racks is the phasor.

The part of the building that looks like a garage (and probably was one, in 1940) is now occupied by a generator. There are several rooms on the main floor used for storage, including the big space next to the transmitter room where the power transformers once sat. (This building has no basement, ruling out the usual spot for the transformers.) There's a bomb shelter near the main entrance, though it hasn't been set up for such use in decades, and several rooms on the south end of the building that were once used as a machine shop, a workshop and as bare-bones living quarters for the engineering staff.

|

|

Upstairs, there's plenty of ventilation going on above the main transmitter room - but the neat stuff is in the smaller attic rooms on either end of the building, where boxes full of old WBOS transmitter logs, antique beacon lights and whatnot await a diligent historian's attention.

As for the towers? They deserve a chapter of their own, and they'll get one in next week's installment. Stay tuned!

(Scheduling note: We're doing a lot of traveling this summer, in search of more nifty sites to show you here at Site of the Week, so Tower Site installments may be delayed or postponed a bit. Thanks for your patience!)

It's almost here - ordering is now open for the brand-new 2006 Tower Site Calendar! Click here for ordering information!

- Previous Site of the Week: FM 128, Newton, Mass.

- Next Week: WBZ: 65 Years in Hull, part 2

- Site of the Week INDEX!

- How can you help support Site of the Week? Click here!

- Submit your suggestions for a future Site of the Week!