|

|

January 27, 2006

KTNQ/KTLK, City of Industry, CA

By SCOTT FYBUSH

Over the years, we've seen some unusual AM tower configurations. There are the few remaining longwires - WSAJ 1340 Grove City, PA and KYPA 1230 Los Angeles, for instance. There are towers in the water, such as KNRY 1240 Monterey, CA and WTIX 690 New Orleans. There's at least one tower painted green and white (Dartmouth College's WDCR 1340 Hanover, NH - and don't worry, it's too short to meet the usual painting requirements.) There are towers in parking lots (you'll find two of them - WSB 750 Atlanta and KTAR 620 Phoenix - in the 2006 Tower Site Calendar.) There are towers on rooftops (you'll find one of them in the calendar, too - WEJL 630 Scranton, PA.)

There's even a directional array on a rooftop: KPIG 1510 Piedmont, CA, whose five-element array is made up of four towers and a dropped wire atop a big warehouse in Oakland.

And then there's...this:

This most unusual AM facility can be found at the corner of Don Julian Road and Sixth Street in City of Industry, California, just off the Pomona Freeway about nine miles east of downtown Los Angeles. It's not a five-tower array behind a warehouse, as you may think at first glance. Nor is it a five-tower array atop a warehouse, as a closer inspection might make it appear.

It is, in fact, a five-tower array that's had a warehouse constructed around it - not just surrounding the entire array, but surrounding each tower base. And, inevitably, our look at this array has to begin with some history:

This site was built in 1975 for KGBS (1020), a venerable Los Angeles broadcaster (formerly known as KFVD) that had spent most of its life as a daytimer, albeit with permission to operate late Sunday nights-early Monday mornings when KDKA in Pittsburgh, the Class I-A station on the channel, was silent. Storer Broadcasting, which owned the station, worked out an arrangement with the Class II-A station on the channel, KCKN in Roswell, New Mexico, to change its directional pattern to allow the Los Angeles facility to go full-time with 50 kilowatts. That, however, required a transmitter site east of Los Angeles, to aim the signal west, away from Roswell and Pittsburgh. KGBS' two-tower site near the Long Beach Freeway in Lynwood, south of downtown L.A., wasn't going to work - and so these five 490-foot towers went up on an open piece of land in Industry. A year after KGBS moved to the new site and went to 24-hour operation, it changed calls to KTNQ ("Ten-Q") and became one of the last big AM top 40 signals to launch in a major market. (It would later go Spanish, still under the KTNQ calls.)

Then the value of the land around the towers started to climb - and in the late eighties, the owners of the site decided to build an industrial park on the land, right around the tower bases. Legendary engineer Ron Rackley was brought in to make it all work, and the solution he came up with involved 1.25 million square feet of chicken wire, lining all the walls and the roofs of each building, all bonded to the ground system underneath. The tower bases themselves ended up in 25-foot-deep wells within the building, lined with copper and accessible only via a ladder leading down from the roof. Some of the guy wires had to be relocated to land on elevated anchors in the parking lot between the two buildings, and the transmitter itself ended up in one of the rental spaces in what became, when it opened in 1990, "Towers Industrial Park."

|

|

Unusual?

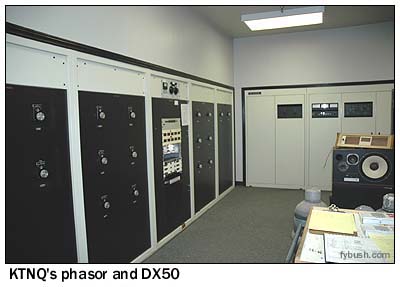

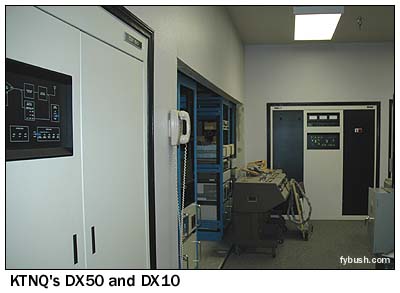

You bet. But it worked, and KTNQ kept chugging away from its

primary Harris DX50 and auxiliary DX10, and life was pretty good.

Its transmitter space in the warehouse building was a sizable

one, with a big garage for the "Fiesta-mobile" remote

truck, a U-shaped transmitter room with the phasor at one end,

the DX50 (and, I think, at one time a Continental) in the middle,

and the DX10 backing up to the garage at the other end.

Unusual?

You bet. But it worked, and KTNQ kept chugging away from its

primary Harris DX50 and auxiliary DX10, and life was pretty good.

Its transmitter space in the warehouse building was a sizable

one, with a big garage for the "Fiesta-mobile" remote

truck, a U-shaped transmitter room with the phasor at one end,

the DX50 (and, I think, at one time a Continental) in the middle,

and the DX10 backing up to the garage at the other end.

Smaller rooms off the main transmitter room held (and still hold) KTNQ's equipment racks, a small office and a bathroom.

Then, in late 1997, Jacor's KXTA (1150) won the contract to carry Dodgers games beginning the next spring. The company had recently purchased co-channel KBAI, Morro Bay and taken it dark, clearing the way for a power increase in Los Angeles. (The station was operating with 5,000 watts day and night from the old KFSG site in Montecito Heights.) And the Dodgers contract required that the games air on a 50,000-watt outlet. Suddenly KXTA had to move fast to make its upgrade a reality in time for Opening Day.

Diplexing with an existing station was a must, and the KTNQ site was the best choice. In the space of just 56 days, KXTA's engineering crew (with chief engineer Mike Callaghan at the helm) turned this site from a single-station facility into a two-station diplex.

|

|

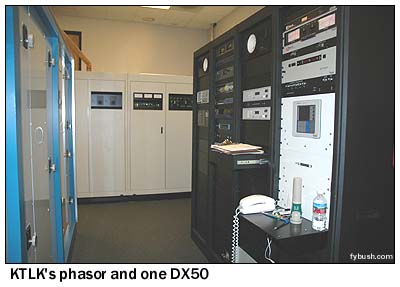

Unable

to reach a deal to lease separate transmitter space within the

warehouse, KXTA worked out an arrangement with KTNQ to rent the

garage. Out went the "Fiesta-mobile," and in came a

very tightly-packed arrangement with a DX50 at each end and the

Kintronics phasor and equipment racks in the middle.

Unable

to reach a deal to lease separate transmitter space within the

warehouse, KXTA worked out an arrangement with KTNQ to rent the

garage. Out went the "Fiesta-mobile," and in came a

very tightly-packed arrangement with a DX50 at each end and the

Kintronics phasor and equipment racks in the middle.

Transmission lines for the two towers that sit amidst the building on the west side of the facility (the one that houses the transmitters) run out from here to the roof and over to each tower. Getting the transmission lines over to the three towers on the other building, across a parking lot, was somewhat more complicated.

The answer turned out to involve trenching under the parking lot, putting in two six-inch PVC conduits carrying the transmission lines (some as large as 3 1/8") and a four-inch conduit carrying the control cables.

At the other end of the parking lot, a cable chase was built up the side of the building, carrying the lines to the roof, where wooden trestles brought them across to the towers.

Installing the diplexing filters and new antenna tuning units next to each tower was another huge (and nerve-wracking) project. The boxes were far too heavy to be slid across the roof to their destinations, and the tangle of guy wires made helicopter delivery impossible. Instead, two cranes were used, one on each side of the huge building, and trolley lines were run from one crane to the other to suspend the boxes as they were moved across to their final homes.

The system was powered

up on February 22, 1998, and has been running ever since, with

50 kilowatts by day and 44 kilowatts by night, delivering what's

now regarded as one of the better AM signals in Los Angeles.

(A pending city-of-license change to Downey and modification

of the pattern promise to improve it even further.)

The system was powered

up on February 22, 1998, and has been running ever since, with

50 kilowatts by day and 44 kilowatts by night, delivering what's

now regarded as one of the better AM signals in Los Angeles.

(A pending city-of-license change to Downey and modification

of the pattern promise to improve it even further.)

KXTA's sports format moved down the dial to KLAC (570) in 2004, and 1150 is now "Progressive Talk" KTLK.

(Mike Callaghan has some wonderful stories and pictures about the 1150 project at his hottips.org website - check it out!)

Visiting the site, as we did in April 2005, is a most unusual experience. The entrance to the Towers Industrial Park is right in the middle of the directional array, and driving between the two buildings puts you under a wire screen that stretches 165 feet from building to building, continuing the ground screen across the open space.

Stand on the stairs that lead into the transmitter space, and you're looking across at the well-concealed cable chase (just to the right of the doorway in the view above) that brings the 1150 transmission lines up from the trench to the roof.

At various points in the parking lot, pillars lift guy-wire anchors up above the truck traffic that's constantly passing through. And if you look up through the screen, there are those towers looming above the buildings.

In 2003, the Los Angeles Times carried a prominent story about this site, reporting that its tenants generally had no idea what those towers were for, or what the screen overhead did (one person told the Times that he thought the screen was there to keep the towers from falling into the parking lot in case of an earthquake, and others thought the towers were there to warn aircraft away.)

Their biggest complaint? Radio reception in these very well-screened buildings (which are effectively giant Faraday cages) is terrible!

Unusual enough for you?

- Previous Site of the Week: KFI, Los Angeles

- Next Week: KBLA, Los Angeles

- Site of the Week INDEX!

- How can you help support Site of the Week? Click here!

- Submit your suggestions for a future Site of the Week!