Site of the Week 9/17/2021: WBZ Turns 100

Text and photos by SCOTT FYBUSH

It started 100 years ago this weekend: after being granted a license by the Department of Commerce on September 15, 1921, radio station WBZ began broadcasting on September 19, 1921 from the East Springfield, Massachusetts factory of its owner, Westinghouse.

As regular readers of this column know, WBZ is a very special place to your editor, who worked there from 1992 until 1997, a span that included the station’s 75th anniversary celebration and a major studio move.

We’ve featured bits and pieces of WBZ’s physical legacy over the years here (heck, we’ve been around here so long that we did a “WBZ at Eighty” feature on this same weekend 20 years ago), but for the centennial, we’re pulling all the pictures and links together in one place to salute this big event.

A few notes at the outset: while WBZ boasts “the first commercial broadcasting license,” that’s really a technicality, since it just happened to be granted its license right as the Commerce Department was introducing that new category of license to account for the rise of radio broadcasting. What WBZ was doing in the autumn of 1921 had been done months earlier by its sister station KDKA in Pittsburgh – and, for that matter, by station 1XE in Medford Hillside, outside of Boston, as well as by stations in Detroit and San Francisco and Madison, too.

And as our history colleague Donna Halper will be quick to tell you, WBZ wasn’t the first radio station in Massachusetts, since 1XE was there earlier, and in the Boston area where more potential listeners resided, too.

But what Westinghouse did better than any of its earlier competitors was to push its radio stations into the view of a wider audience, using its marketing machinery to turn a hobby and a science experiment into a business.

For the first few years, it all happened at the East Springfield factory, from a transmitter shack on the roof and a makeshift studio. (That very first broadcast on Sept. 19, 1921 was actually a remote, coming from the “Big E” expo down the road.)

Change and growth came fast: by 1924, WBZ had spawned a synchronous transmitter, WBZA, 100 miles to the east in Boston. By 1931, the stations had swapped: the Springfield transmitter was still 1000 watts and had become the synchronous outlet as WBZA, while the WBZ calls and main studio went to Boston.

A new 15,000-watt transmitter site went up in Millis, southwest of Boston, establishing WBZ (by then on 990 kc) as one of the biggest clear-channel signals in the country.

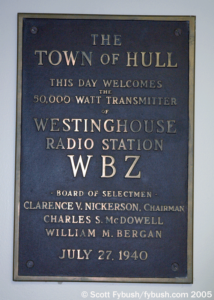

As with so many of those clear-channel signals in the 1930s, WBZ took advantage of a change in FCC rules about high-power AM tower siting to move closer to Boston. In 1940, Westinghouse opened a new 50,000-watt transmitter facility right at the water’s edge in Hull, southeast of Boston.

The Hull plant was unusual for a class I-A clear channel: in order to maximize power over Boston and its suburbs, it used a two-tower directional antenna that concentrated the signal to the west, putting a null eastward over the Atlantic Ocean.

The facility that Westinghouse dedicated in Hull on July 8, 1940 was intentionally modest in design. In a time when many transmitter buildings were Art Deco showplaces, the Hull facility was built to resemble the other Cape Cod-style homes on the residential street it faces.

To the north of the transmitter building, two 500-foot towers were erected, each a half-wave tall on the station’s frequency of 990 kHz, and spaced a quarter-wave apart. (The March 1941 shift to 1030 would make the towers, and their spacing, slightly more than half-wave and quarter-wave, respectively.)

To the west, a field of telephone poles stretched into the marsh, carrying the antennas for Westinghouse’s shortwave operations. (The shortwave station associated with WBZ, first at Springfield and then at Millis, had used the calls W1XK, then WBOS; with the completion of the Hull facility, Westinghouse moved its Pittsburgh shortwave transmitters, then operating as WPIT, to Hull as well. The WPIT calls were retired early in 1941 and the facility was then known solely as WBOS for its remaining years.)

Hull also became the home, for a time, of WBZ’s FM operation, which also moved from Millis. The antenna for W67B (46.7 mc) would have most likely been mounted on one of the AM towers; it’s hard to imagine that coverage into Boston from such a distance would have been very good, and the FM was quickly relocated to the new TV tower at Soldiers Field Road as that facility was completed in 1948.

After almost twenty years of nonstop motion, WBZ had found a permanent home for its huge AM signal, and a most successful one at that. With nothing but salt water between the bases of its towers and the shoreline of Boston, the Hull site provided – and continues to provide – a booming signal to the city itself. With no nulls to the south and west, unlike Boston’s other AM stations, WBZ blanketed the rural areas that would someday become booming suburbs, and which other AMs would struggle to reach successfully. The coastal site gave WBZ a huge reach along the water, pumping a strong daytime signal north into Maine and south into Rhode Island. Its clear channel and tall towers gave WBZ’s night skywave signal a spectacular reach, with a particularly strong signal into New York City after dark. Only the outer reaches of Cape Cod, on the back side of WBZ’s directional pattern, suffered from a less-than-optimal signal – and in 1940, who knew that would be important?

(One more historical digression: It’s not commonly known that the Cape Cod problem was almost solved. As WBZ and other clear channel stations pressed for much higher powers well into the sixties, Westinghouse informed the Congressional subcommittee studying the situation that it would, if granted 750 kW, build a new WBZ transmitter plant in Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod, some 50 air miles from downtown Boston. Such construction in an environmentally-sensitive area would be unimaginable today; as it turned out, Congress rejected any increase in power for the clears, making the issue moot.)

The Hull site was also an excellent one for the WBOS shortwave operation, which targeted its signals to listeners in Europe and South America. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, WBOS and the other commercial shortwave stations around the country were commandeered by the Office of War Information, which took over programming them with what would eventually become the Voice of America. Westinghouse continued to operate the WBOS facility under contract to the government until 1953, when its usefulness came to an end. The transmitters went down the coast to another private shortwave operation, WRUL in Scituate (later WNYW, and now Family Radio’s WYFR in Okeechobee, Florida), while the antennas in the swamp were left to rot. As late as 1999, many of the old telephone poles that held WBOS’ antennas could still be seen behind the WBZ transmitter building, though most were removed during tower construction that year.

It’s been a while since we’ve been out to Hull (an omission we’re hoping to rectify very, very soon), but let’s revisit the tour we took in 2005, which we’ve excerpted liberally here, albeit with larger and better images.

The building on Newport Ave. looked then – and looks now – little different than it would have 81 years ago: from the front, it resembles the other small homes on the street, with the chain-link fence and the big transformer out front some of the only clues that something different is happening inside. The entrance these days is at the back of the building, where it rises to two stories.

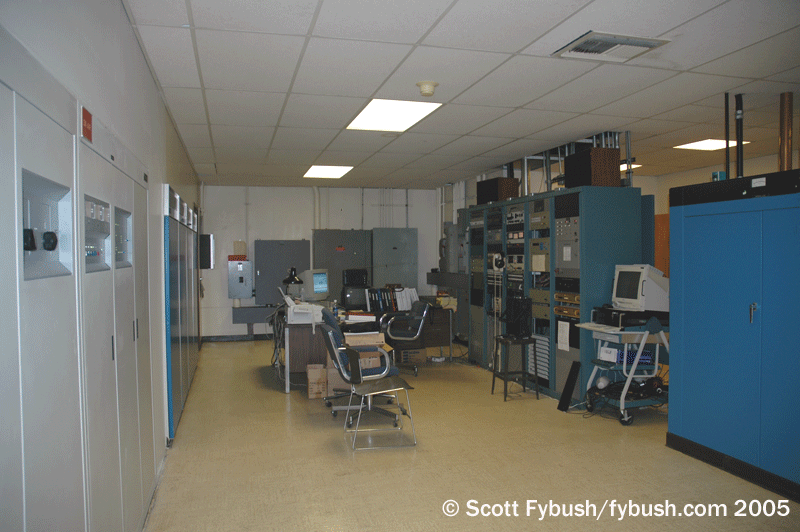

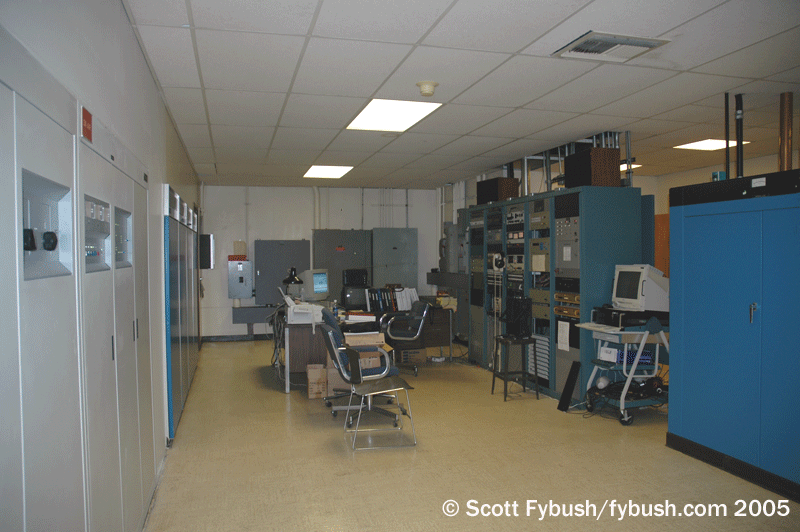

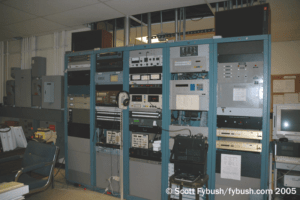

Walk inside, and you’re facing right into the main transmitter room, where a classic Westinghouse 50HG gave way to a pair of Harris MW50s in the 1970s. By 2005, one of the MW50s had been replaced by a DX50, with the other remaining as backup, and that’s since changed again.

For a long time, WBZ was one of the few stations with a completely separate backup transmitter site as well; at its former Allston studios, there was a DX10 feeding a folded unipole on the STL tower in the parking lot, a facility that saw a lot of use during the tower rebuild in Hull in 1999.

Across from the transmitters sat the big rack of processing and STL gear (by 2005, the signal arrived by T1, after many years of struggles with a long and challenging microwave path from Allston that suffered from having downtown Boston in the way, not to mention the propagation issues over all that water), and next to the racks was the phasor.

The part of the building that looks like a garage (and probably was one, in 1940) was later occupied by a generator. There are several rooms on the main floor used for storage, including the big space next to the transmitter room where the power transformers once sat. (This building has no basement, ruling out the usual spot for the transformers.) There’s a bomb shelter near the main entrance, though it hasn’t been set up for such use in decades, and several rooms on the south end of the building that were once used as a machine shop, a workshop and as bare-bones living quarters for the engineering staff.

Upstairs, there’s plenty of ventilation going on above the main transmitter room – but the neat stuff is in the smaller attic rooms on either end of the building, where boxes full of old WBOS transmitter logs, antique beacon lights and whatnot awaited (and may still await?) a diligent historian’s attention.

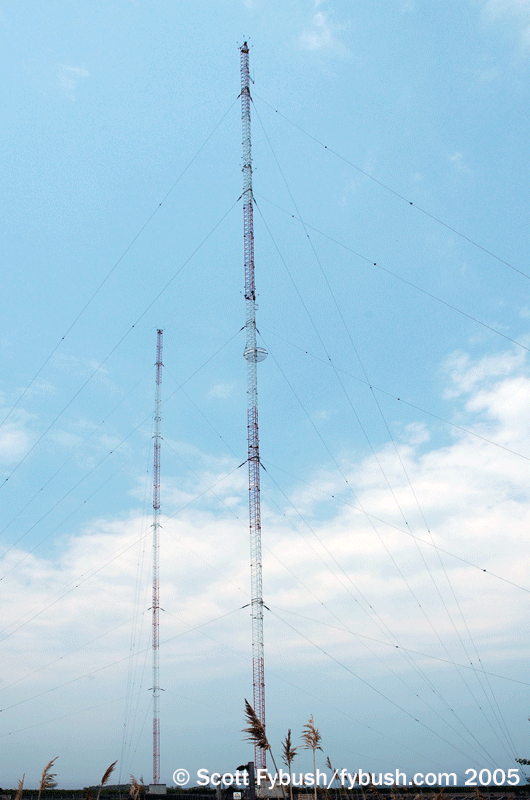

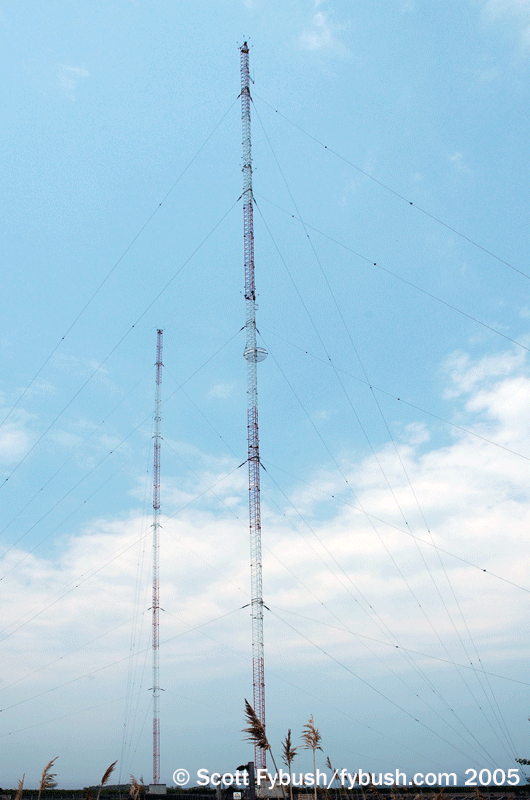

So let’s head out the back door and down the catwalk that stretches over the swampy land behind the building and out to the two 520-foot towers that dominate the landscape in this part of the world.

These towers were half-wave on 990 kHz, the frequency WBZ used in 1940, and that makes them just a bit over half-wave – 188.5 degrees – and a bit more than a quarter-wave apart (93.6 degrees) on the 1030 kHz frequency that WBZ moved to in 1941. Those details aside, this is as basic a two-tower cardioid array as it gets.

What’s not so basic is the process of dealing with the effects of six decades of salt air on these towers, and that’s a challenge that the WBZ engineering staff faced a few years back when it came time to renovate the site.

In an ideal world, the aging towers would simply have been taken down one at a time and replaced with new steel. But this is the 21st century, and as at so many other sites in densely-populated areas, the zoning challenges put in place by the town (not to mention the environmental impact such a project would have had on this wetland area) meant that if the original towers ever came down, there would be almost no chance of putting them back up.

At the same time, WBZ still had to address the very real problem that the steel in the towers was in bad shape in some areas – and that’s not even mentioning the 60 year old insulators at the base of each tower or the aging tuning networks.

Some of the nation’s top engineering consultants were put to work on the problem, and here’s the solution they arrived at: by replacing the existing two levels of guy wires on each tower (which didn’t reach anywhere near the top of the towers) with five levels of guys, the towers could be stabilized against just about anything nature could throw at them.

Through much of 1999, WBZ operated from its 10 kW backup transmitter at its studio site in Boston’s Allston neighborhood while the work proceeded out at Hull.

New base insulators were installed, and workers moved up and down each tower in tented enclosures to contain the lead paint that was released as each tower was carefully restored to stable condition. In effect, each tower was rebuilt in place, and by 2000 WBZ was back to full power from the rebuilt Hull site, complete with new tuning houses (replacing the old ones that had been directly beneath each tower.)

And speaking of those tuning houses – take a look at the photo above, showing the support frame that keeps each one elevated over the swamp below. It’s hard to imagine much better ground systems than this one, which connects directly to the salt water of Massachusetts Bay.

A few coats of paint and a new transmitter later, things in Hull are otherwise relatively unchanged these days, from what we hear – an engineer from 1940 would more or less recognize this site.

But everything else about WBZ has changed dramatically in the last decade, as loyal NERW/Site of the Week readers know.

Someday, we really ought to resurrect all our pictures (shot on film!) from the years when we worked at 1170 Soldiers Field Road, WBZ’s studio home from 1948 until 2018. Even after many years of diligent study of WBZ’s history, there’s still a lot I don’t know about how that building evolved, and in particular what the original radio studio layout was for WBZ’s first few decades there.

By the time I arrived in the early 1990s, it was to a somewhat aging facility that had last seen a significant renovation sometime in the mid-1970s, when air talent began operating their own consoles. That L-shaped studio cluster included a main air studio with a big window looking west to the AM aux tower in the parking lot, a news booth facing into that studio, a master control area looking into both of those studios, and three production studios flanking the air studios. (At least one had been the home of WBZ-FM in its rock era of the early 1970s.)

The piece of WBZ’s history we can tell in the most detail -and we will, someday – is the 1996 building expansion that added a new eastern wing to the original 1948 footprint. Back then – and for most of WBZ’s history at “1170” – radio was mostly on the west side, while the TV control rooms and studio took up the east side. It was a big internal culture change when the radio newsroom and studios were moved across the building, taking up one wall and about a third of the floor space of an expanded radio/TV newsroom.

You can see that version of WBZ in a lot of detail in this RadioInsight piece I wrote in 2018, which took a look at the station’s last moments in the building after 70 years. The move, of course, was precipitated by the split in ownership in 2017: while WBZ-TV stayed with CBS, the successor to Westinghouse, WBZ(AM) ended up being spun off to iHeart, which relocated its studios to an expanded facility up in Medford.

You can see what that facility looked like on opening week in the second part of the RadioInsight piece, which includes photos and video of the shiny new studios – go check it out!

To bring our story to conclusion, a few more bits of history have gone away over the years, too: in 2011, the East Springfield towers were taken down ahead of the demolition of the old Westinghouse plant, 49 years after they’d last broadcast a WBZA signal. (The site was to have been redeveloped into a shopping center but instead remained vacant for years.)

And as WBZ-TV also prepares to leave the 1948 studio building for a smaller, newer plant next door, the old AM auxiliary tower came down a few months ago, too. For now, the only physical legacy of WBZ radio’s 70 years there, if you know what you’re looking for, is the office of the building facility manager, in what used to be the main WBZ radio air studio. One day soon, that too will be gone, as WBZ rolls into its second 100 years of service to New England with more focus on its future than on its glorious past. (Aren’t you glad we’re here to remember?)

Thanks to all my WBZ colleagues over the years!

THE TOWER SITE CALENDAR IS SOLD OUT!

In just a few months we’ll have information about the 2025 Tower Site Calendar.

Until then, please take a look at the books for sale in the Fybush Media Store.

And don’t miss a big batch of IDs next Wednesday, over at our sister site, TopHour.com!

Next week: Pittsburgh